by Susan Chock Salgy

Finding ancestral records in China is a complex endeavor. Sometimes it comes together neatly and you are done in a month. Other times it takes patience, persistence, prayer, and a miracle or two. Finding my great-grandmother’s ancestors took three years, heroic effort from a Zhuhai Museum curator, and some unexpected miracles. It’s not over yet.

The Year of the Women

MARCH 2021 — Two years after we began working together, Louise and I made a decision that shifted the focus of our research dramatically. This was to be the most important pivot in our entire 5+ year project.

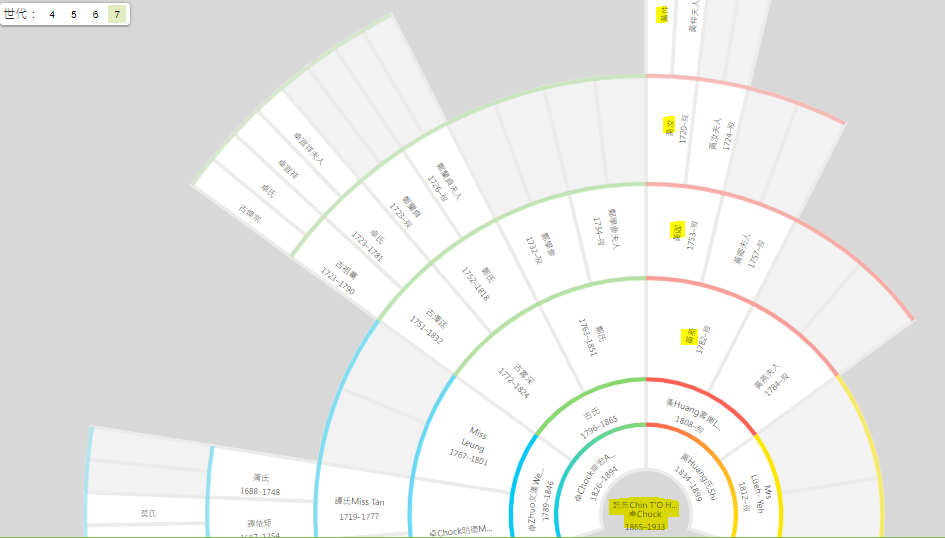

After reaching some important milestones in my Chock genealogy project, I was staring at a chart of Chock Chin’s ancestors and was struck by the extreme contrast between the astonishing superabundance of his father’s lineage–which, thanks to Louise, now stretched back to 2700 BCE–and the extreme dearth of his mother’s lineage–which started and stopped with her own name: Miss Huang of Tung-An (黃Huang氏Shi).

Of course, I had noticed the disparity before, but never did the raw injustice of my great-grandmother’s genealogical privation become so clear to me. We had just spent two years non-stop, devoting tremendous effort and resources to fill all the empty chairs at the 4700-year-long Chock men’s table. And spared no more than a passing thought for all the women who joined them at those chairs. It was time for a change.

Shifting away from the Chock/Zhuo clan, we began searching for the clans of the women who had married into my Chock/Zhuo clan over the long span of these records. The mothers and grandmothers. The aunties and sisters-in-law. Louise and I affectionately call 2021 the “Year of the Women” although it is still going strong 2 1/2 years later.

Although searching for women’s clans is not supported by the patrilineal structure and paradigm of Chinese families and records, and is directly contrary to the practices of Chinese genealogists, a tree with only a paternal line feels terribly incomplete and unbalanced to me. All Yang, no Yin.

The wives, mothers, and sisters-in-law who joined the Chock family were first daughters. They endowed the Chock clan over many centuries with children that carry the Chock blood enriched with the heritage of their own long bloodlines. And although they will bear the Chock surname, they inherit the gifts of two houses. Every woman who marries and takes her husband’s surname understands this.

For me, it seemed the time had come to honor the contributions of the mothers by searching for their own ancestral records and adding them to the Family Search tree as vital participants in the family history.

Swimming upstream to find Chinese women’s records

Louise didn’t think we’d get very far based on her experience with Chinese records and tried to steer me away from what she thought would be a terrible waste of time and money. But she was willing to try swimming upstream to look for them if I really wanted her to. Which I did. So she rolled up her sleeves and set to work with her trademark persistence and systematic attention to detail.

She painstakingly re-visited all the Chock records we had acquired, looking for clues about the fathers of any of the brides. What she needs is enough specific information to have been entered into the Chock Zupu about the bride’s father–his birthdate and village and ideally his wife’s surname–to identify him as a distinct individual in his clan records.

If she spots a bride documented with that information (very rare, but not completely impossible), she can begin a hunt for the father’s clan zupu, somewhere in the vast collections at Family Search.org, Ancestry.com, Shanghai Library, etc. She will need long-term access to the records, so she must be able to download a digital copy, or print a PDF. If the record has not been collected by one of these record aggregators, she will try to find a copy for sale at rare bookstores in mainland China — which has worked surprisingly well for us.

But very often we find that the zupu we need is available only as a fragile original, or a recreated record being safeguarded with great suspicion and mistrust of outsiders within the ancestral village. This is a direct consequence of the widespread destruction of the original clan records and the ancestral temples that housed them during the 1960s Cultural Revolution. In those cases, she relies on her two best allies in the field: Zhuo Bing Quan, and Mr. Luo. They will travel to the village and work with the clan elders to obtain a copy of the zupu for Louise.

Once she finds the right zupu, she can then search through the entries for any males who could reasonably be the right age to be the bride’s father, and then see if any of them married one of his daughters to the right man of the Guan Tang Chock clan on the date recorded in the Chock Zupu.

There is nothing easy about this, even for someone as experienced as Louise. The reason is simple. No one is supposed to look for personal information about a woman (including her given name) in the first place. And certainly not in her husband’s clan records. So information about her parents, if noted at all, is not entered prescriptively as we do with Western records. If it’s there at all, it’s more of a bonus tidbit added by clan record keepers to showcase a particularly impressive clan alliance and thus burnish the reputation of the Chock clan.

Happily, it was also considered an honor to marry into the Chock clan during much of our long history, so the bride’s clan elders would also note her marriage to a Chock male in their records. This little “bragging rights” tradition has helped Louise pinpoint marriage alliances from both directions. But more often than not, there is simply not enough information to narrow down the options and pinpoint the bride’s father (and thus find her entire ancestral line) in the clan zupu.

Finding Chock Chin’s Huang ancestors

But as I said, this was a quest that required miracles. So here’s how it happened.

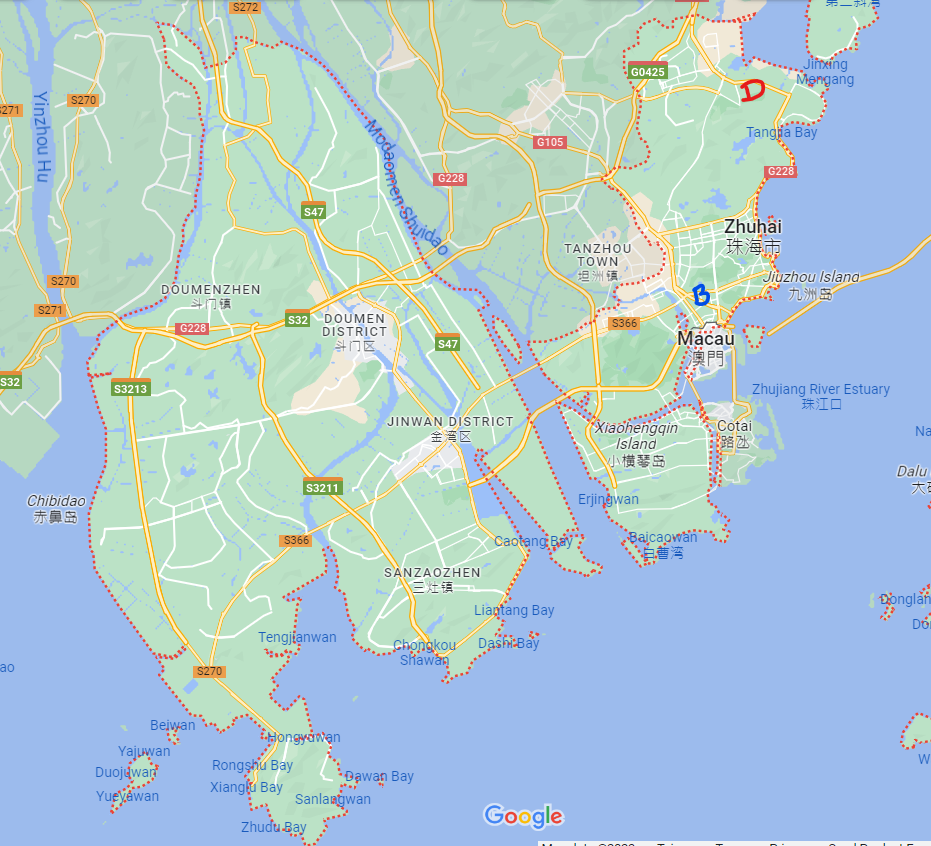

Chock Chin’s mother was Miss Huang of Dong’an (aka Tung-An). That much we knew from the entry in the Guan Tang Chock clan zupu. It was also noted in the abridged jiapu Chock Chin had been given when he left the village as a young man in search of a way to earn money for the family. So this was a good place to start.

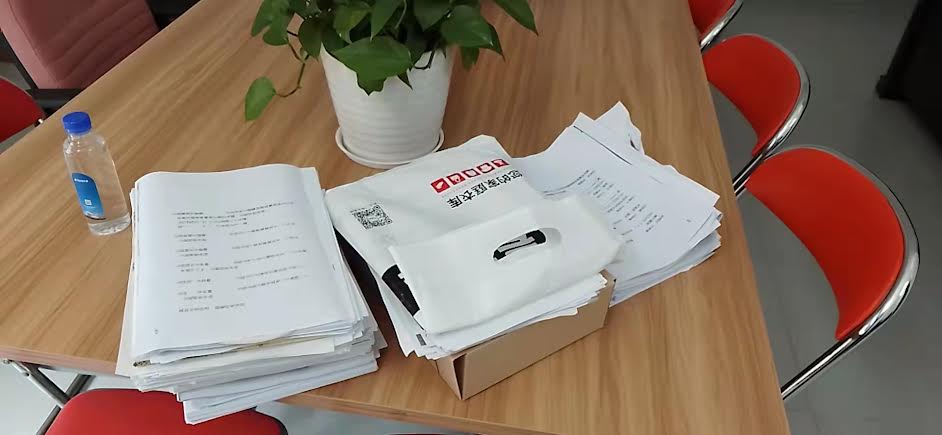

Louise asked the Guan Tang Chock clan historian, Zhuo Bing Quan, to visit Dong’an to search for my great-grandmother’s Huang clan records. He was disappointed to discover that the clan had attempted to reconstruct the pedigree info (destroyed in the Cultural Revolution along with a lot of other clans’ records) but it was incomplete and unorganized. All the information they had gathered was written on piles of loose paper which was stacked together in random order. No one had found a way to organize it or bind it together in any logical order.

Zhuo Bing Quan learned that the Huang clan had at some point hired a genealogist to compile a zupu from this mass of paper, but he returned everything a month later without having made any progress. He told the clan elders that it was an impossible task.

Mr. Luo Takes a Look

MARCH 2022 — after repeated (gentle) requests from Louise that he try to get the Huang records from Dong’an, Mr. Luo of the Zhuhai Museum agreed to meet Zhuo Bing Quan in Dong’an to take a look at the jumble of pages.

The clan was amazed that someone from the Zhuhai Museum had an interest in their records and was willing to travel to the village to see if they could be put into usable order. Mr. Luo was anything but optimistic about them. He was convinced he would not be able to unscramble them in the time available to him, but as a favor to Louise he agreed to at least look at them.

March of 2022 was right in the thick of the Covid lockdowns in mainland China. As you may recall, China had zero tolerance for Covid cases for three years, and during that time they tested their populace daily. If a few residents of a city tested positive, the entire city would be quarantined, preventing travel in or out and causing a great deal of churn in people’s lives. At this time, Dong’an had been under Covid quarantine for many weeks so we didn’t know if Mr. Luo would even be able to go look at them. But the quarantine was suddenly lifted on the day he had planned to go, so he went.

The day before he left, Louise asked him if he would help compile the zupu once he got the papers and he replied, “Possibly not.” This is the polite way for a refined Chinese person to respond to such a question when he really means, “No way!” Mr. Luo had learned from Zhuo Bing Quan exactly how bad their condition was. Louise knew exactly what he meant.

Feeling this may be their last, best chance to turn this chaotic mess into a real zupu, the clan leaders gladly entrusted the whole collection of paper records to Mr. Luo and he returned to his home in Bai Shi, Zhuhai. The next day Dong’an was locked down again for another Covid quarantine which lasted for several weeks. Somehow he had miraculously threaded the needle — arriving on the one day that people could enter the village from outside and leave again. Louise and I took it as a hopeful sign.

At that point Mr. Luo was confident he would discover the job would require more time and resources than he could spend on it and he could make a polite excuse. But when he sat down to take a closer look at the papers in his office the next day, something changed his mind. He decided to give it a try. We count that as a miracle too.

After a month of very intense effort he was able to compile them into four volumes and make a digital file of the partial zupu to send Louise. The Huang clan elders were thrilled to have a usable record — even if incomplete — after so many years of trying.

After this roller-coaster ride, however, we faced a huge disappointment. To Louise’s dismay, neither my Huang ancestor (Huang Shi’s father, Huang Lue Ye) nor my cousin Gerry Goo Nihipali’s Huang ancestor (Huang Jie Shi) were found in the reconstructed four volumes. Of the 8 total volumes that had been in the original Huang Zupu before it was burned to ashes in the Cultural Revolution, only 4 were covered on the loose paper in the boxes.

(NOTE: Our family is very closely related to the Nazhou Goo/Gu clan, of which Gerry is a descendant living in Laie, Oahu, Hawaii. Our Chock, Hee, Huang, and Goo lines intertwine with Gerry’s at multiple points.)

Out of Canada, another Miracle

MARCH 2023: One year later, During the Chinese New Year holidays, the Dong’an Huang clan held a great clan reunion at their Grand Ancestral Temple. They had over 300 tables brimming with guests.

One of the attendees who made his way to the ancestral village to celebrate was a Huang descendant who now resides in Canada. Although he doesn’t read Chinese, he found Dong’an fairly easily, because the village name appears on the family history book his ancestor took with him when he left Dong’an 100 years ago.

All this time his family has been safeguarding this precious Huang family record and continuing to record the details of their expanding family. He brought that book with him to the celebration and showed it to the clan elders. To their astonishment and joy they recognized that it was a copy of one of the lost original volumes. But this time, still intact as a book, rather than loose pages of piecemeal data reconstructed over time.

He presented a copy of this precious volume to the clan elder. And the clan elder, now considering Mr. Luo to be the only person qualified to handle and digitize their clan records, contacted him with this newly found volume.

This turned out to be Volume 5 — one of the four missing volumes of the original zupu. And my ancestor, Huang Shi’s father, Huang Lue Ye, was found with his ancestral line in that volume. But not Gerry’s.

Within a few days, the Canadian Huang sent another exciting piece of news. Upon returning home, he was contacted by one of his relatives whose ancestor also migrated to Canada. He turned out to have another volume of the Huang zupu. They made a copy to ship to the clan elder. This one proved to be volume 6 of 8.

Mr. Luo was given that additional volume to digitize and, of course, he sent the digital file to Louise. To our great delight, we found that Gerry’s ancestor, Huang Jie Shi is documented in volume 6.

As Louise said, “This is a gift from Heaven, and miracles happen. “

Gerry has one more ancestor of Dong’an who is not in any of the 6 volumes that have found their way back to Dong’an. But I’m guessing pretty soon a Huang descendant somewhere is going to remember something about an old trunk, or find a pile of boxes in their grandfather’s attic, and one thing will lead to another. I’m looking for the last two volumes to turn up next March. Something about March is magical for the Dong’an Huangs.

Huang Shi has her family at last

The best part of all of these stories is when we add long-lost family members to the empty places in the family tree. Here’s the fan chart showing 6 generations of Chock Chin’s mother’s line. Before we had these records, the spaces were all gray and empty above Huang Shi. Now that Louise has carefully added all of the generations chronicled in Volume 5 that returned to Dong’an for Chinese New Year, my great-grandmother’s line reaches back to Huang Zhao ~107 BC and his wife Liu Shi ~103 BC.

I think this is the best way to honor the woman who made such a huge sacrifice that paid off magnificently for her family, and for all of us. Entrusting her best treasure, her first-born son, to the wild sea and all the perilous adventures that waited for him — together with all of us, his unborn family — in the distant Kingdom of Hawaii.