Not all the Chocks who left Guan Tang Village at the tumultuous turn of the century chose Hawaii as their new home. Many factors contributed to that choice. But it was a very tactical decision — you went where you could find safety and a job.

Typically you chose a place because relatives — perhaps your mother’s or father’s siblings — had gone there before you, and knew there were opportunities there. (My grandfather, Chock Chin, went first to K’au on the Big Island to work at the urging of his mother’s relatives working there.) Relatives were happy to have more relatives around, and might help you find a job and a place to live. For the Chinese emigrant, those family networks made the transition to a new world bearable, but not necessarily easy.

Being Chinese in the hostile California in the late 1800s was not the same as being Chinese in the Kingdom of Hawaii. But being a young Chinese mother who is suddenly thrust into lonely poverty when her husband dies — that was the same kind of awful no matter where you lived. When you look at the histories of such women, you find incredible examples of sacrifice, fierce determination, and a core of strength that is revealed and enhanced in that endless struggle.

For example, here is a look at the life of Chock Gum Yip — “Golden Leaf” — a daughter of the Guan Tang Chock clan who migrated to San Francisco in 1885 when she not yet 20 years old. We are indebted to her great-grandson, Gregory Kimm, for sharing this account with us.

About Chock Gum Yip — “Golden Leaf”

By Gregory Kimm

Chock Gum Yip 卓金葉 (“Golden Leaf”) was born on October 2, 1867 in Koon Tong/Guantang Village 官塘村. Little is known of her family.

She had bound feet, leading her youngest child, my maternal grandmother, to believe that she came from a wealthy family, but perhaps her family was not wealthy and her feet were bound simply in the hope that she would be an attractive bride. In any case, both her parents died when she was very young.

She came to the United States in 1885 at the age of 19 (according to Chinese reckoning) and not long after, married Sue Joung 蘇仲, a shoemaker from the village of Pak Shan/Beishan 北山 — which was near her hometown of Guantang Village.

Gum Yip and Sue Joung, residents of San Francisco’s Chinatown, had three children: a son, Dai Ping 帝平 (Frank), born in 1886, and two daughters, Loh Sun 羅新, born in 1889, and Loh Chun

羅珍 (Lily, my grandmother), born in 1894.

When their youngest child, Lily, was just a year old, Sue Joung died, leaving his widow as the sole provider for the family. This life change necessitated the unbinding of her feet.

Gum Yip eked out a living as a seamstress at home, sewing clothing for Chinatown residents. Her children helped, the whole family working together at the dining table, under dim lighting.

When my grandmother Lily was seven years old, she got the responsibility of hemming the bottom of the legs of the Chinese-style pants her mother sewed. But years earlier, this desperately poor

family almost lost their youngest helper. When Lily was about two years old, an uncle advised Gum Yip to accept the offer of a wealthy couple that wanted to buy her youngest child.

The people arrived one day with blankets to wrap up Lily and take her home with them. Lily’s older brother and sister held on to her and tearfully pleaded with their mother, “Don’t sell Mui Mui (Little Sister)!” So Gum Yip changed her mind.

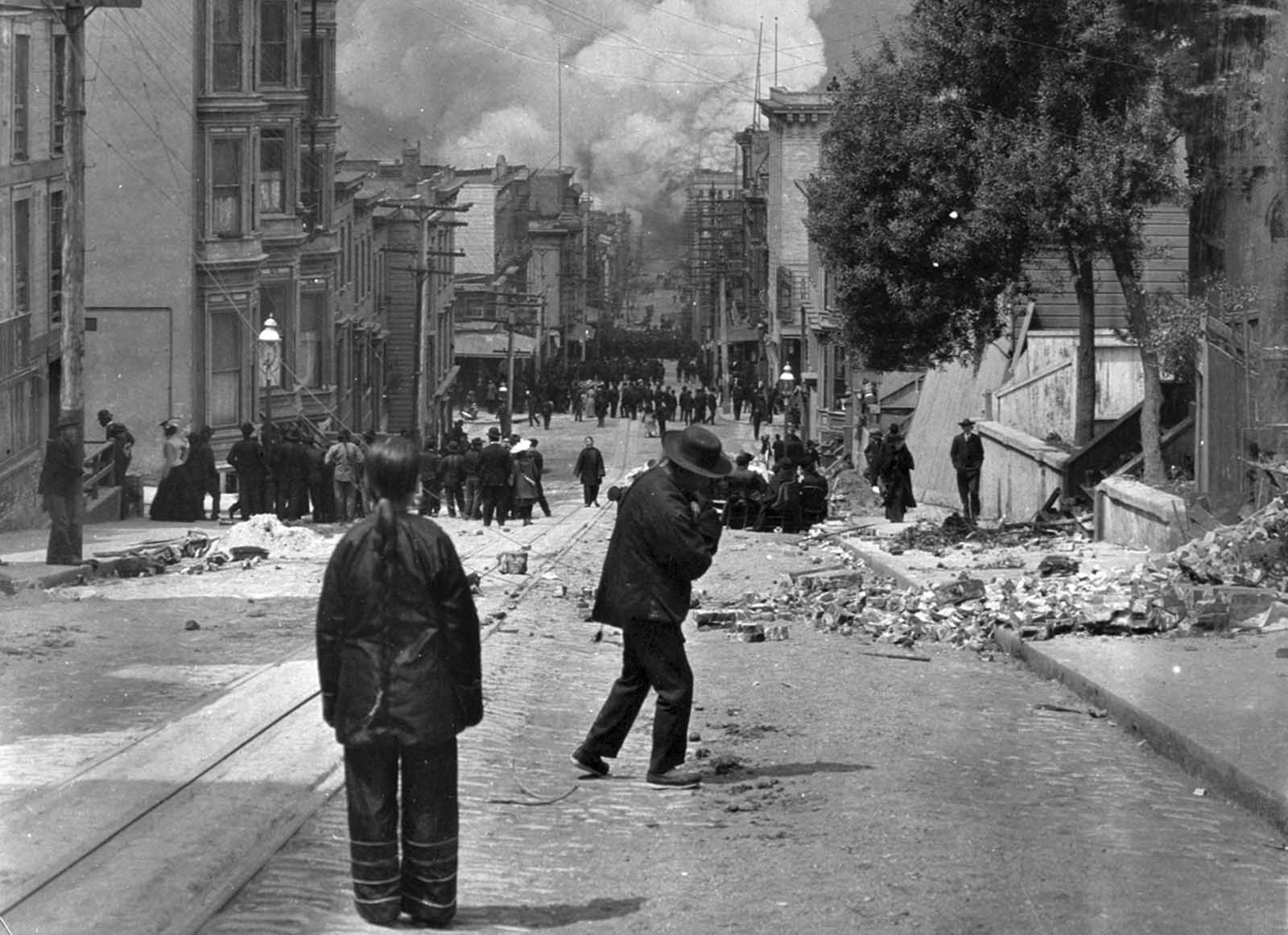

The family lost all their possessions, including their only photo of their father, Sue Joung, in the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906, but they survived, eventually escaping to Oakland with

many other Chinatown residents.

Subsequently, Gum Yip moved to the California’s Central Valley, accompanied by her children. She died of pneumonia at the age of 48/49 on July 3, 1916, in Fresno, CA. Her remains were reinterred in China in 1931 but the location of her grave is now unknown.

Gregory Kimm

1/24/2026

The Impact of the Great San Francisco Quake on the Chinese

“The official census of 1900 recorded some 11,000 Chinese living within San Francisco’s Chinatown, but the real figure was probably 25,000 or more.

Chinatown was both a thriving, self-sufficient community and a gilded ghetto, a bastion of Chinese culture and an expression of the systematic racism in the United States that legally prohibited Asian people from living anywhere else.”

Learn more:

The Great 1906 Earthquake and Fire

1906 Earthquake– Chinese Displacement

Earthquake: The Chinatown Story