Tang Zi Ying Jiapu

Susan Chock Salgy

There are nine volumes of the Tang Zi Ying jiapu. Volumes 1 and 2 are pedigree charts, Volume 3 contains prefaces and individuals’ details, and Volume 4-9 all contain individuals’ details.

Our relationship to the Tang clan

The pedigree chart of Chock Chin to Tang Jian Tian

Chock Chin’s 4th great-grandfather was married to a woman from the Tang clan (Miss Tang). So in March 2021, when we began to research the female genealogical lines, our genealogist Louise Skyles began to search for a Tang jiapu that would contain the family records of our Miss Tang.

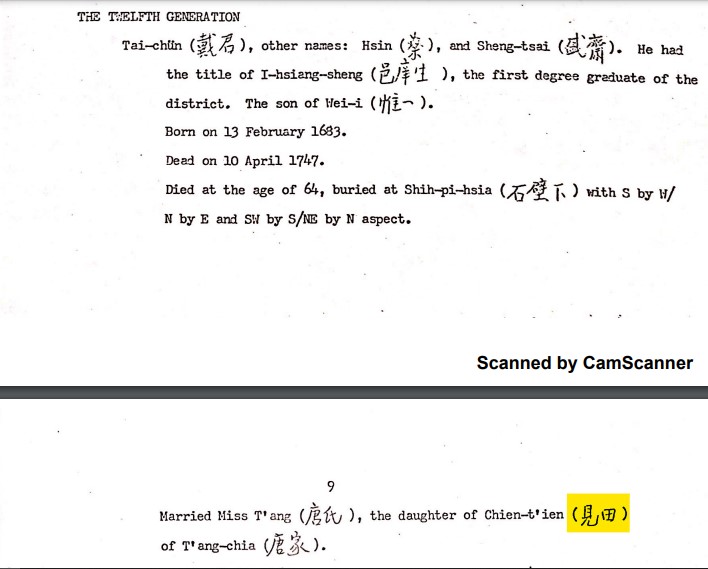

All we knew about Miss Tang at that point was the brief information that was contained in the abridged edition of the Guan Tang Zhuo jiapu that Chock Chin had brought with him to Hawaii when he left China. Here’s the way that appears in our English translation.

Tang Jian Tian唐見田 in Chock Chin’s abridged jiapu (English translation)

Women in Chinese Records

If you look closely at the record, you’ll see that information about the husband is extremely detailed in the jiapu, while the wife is really more of a footnote. This is not unique to our jiapu. Information about the women (mothers, wives, and daughters) in Chinese records is very limited. They are typically just mentioned by their surname, as Miss Tang, Miss Xu, etc.

This is one aspect of this profoundly patriarchal society that is very problematic for Western genealogists. Chinese genealogists are content to focus on the males of the clans because traditional Chinese records almost exclusively supply details about the males. (In fact, more than once Louise has had to explain to colleagues why she is bothering to hunt for the families of the women in this family tree. She now just shrugs and smiles, and says her client is American, and for some reason she really wants to know about the mothers as well as the fathers in the family.)

In most Chinese genealogies the females appear pretty much as supporting characters — necessary but undistinguishable props that support the males. You will see them listed only by surname, appearing meekly as the mothers of, wives of, concubines of, or daughters of the men whose presence and place and dynastic value in the family is indisputable, and therefore worthy of full documentation.

In this particular record, we are given three different names for the husband, plus his title and academic achievement. We are given his father’s name. We have his full birth and death dates, his age at death, and details about his burial place and tomb orientation. We are even given the name and village of his father-in-law. As for his wife, we simply get: Miss Tang.

About the Tang Zi Ying Jiapu

After a series of remarkable events, which I will document in a separate article, Louise was able to locate and purchase the full 9-volume Tang Zi Ying Jiapu from a bookshop in China. The only reason she knew which Tang clan to research was because Miss Tang’s father’s name and village were listed in our jiapu. This was both lucky and unusual. Most of the women in our jiapu do not come with any such clues about their family of origin. (Perhaps the Zhuo clan was proud of this alliance with the prestigious Tang clan, and wanted to document it in the jiapu.)

Tang Jie

Customarily, when a branch of the clan relocates to a new village, a new jiapu is created and named after the ancestor who established the family in the new hometown. This was the case here. Louise said:

“Tang Zi Ying Jiapu was named after the first Tang ancestor who moved to Tang Jia Village. Zi Ying moved to Tang Jia Village, Xiangshan, Guangdong in 1394. He had six sons. The eldest son moved to the nearby village Ji Pai, the second and the fifth stayed in Tang Jia Village, the youngest moved to Dong Wan, and the third and the fourth sons had no heirs.”

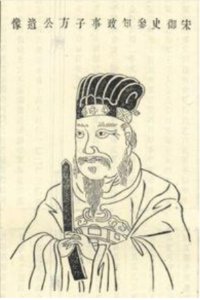

“In the jiapu, the first ancestor was Tang Ju Jun, who was also known as Tang Shao Yao. He lived in Zhuji Alley, Nanxiong, Guangdong, and later escaped to Xinhui around 1279 due to the war. Tang Ju Jun was the 9th descendant of the famous prime minister of the Song Dynasty, Tang Jie (1010-1069).”

![]() Here is Tang Ju Jun in our FamilySearch tree.

Here is Tang Ju Jun in our FamilySearch tree.

“Tang Jie was born in a very prestigious family, and his family tree could be traced back to the Spring and Autumn Period, a period in Chinese history from ~ 771 to 476 BCE.” Learn more at Song Dynasty Biography Index

![]()

Here is Tang Jie in our FamilySearch tree.

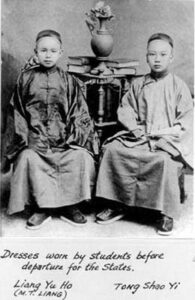

Another famous Tang: Tang Shao Yi

Louise wrote: “The Tang clan of Tang Jia Village was well known in the area. While most of the villagers in the area just barely survived and went overseas to make a living, the Tang clan sent their members overseas to study and learn new skills to be used to benefit China. One of the most famous members of this clan was the first prime minister of China: Tang Shao Yi (1862-1938).”

![]() Here is Tang Shao Yi in our FamilySearch tree.

Here is Tang Shao Yi in our FamilySearch tree.

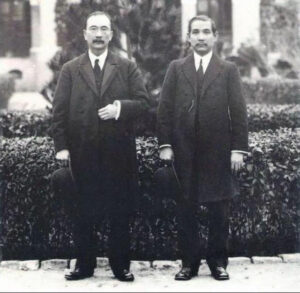

Tong Shao-yi, right, and Liang Yu-ho (Liang Ruhao) before departure for the US [Photo courtesy commons.wikimedia.org]

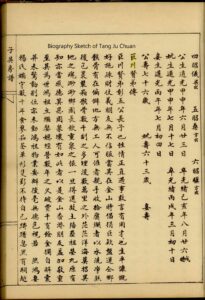

His father’s biography sketch in the Tang Zi Ying Jiapu provides an extraordinary example of this generosity, which extended far beyond his family and friends. On a business trip to San Francisco, he saw that many Chinese who had migrated to California as single men to work– prohibited by law from bringing their families–had died in that foreign land without anyone to make sure their bodies were sent back to China to be properly buried in their village. This traditional desire of Chinese to be buried in their ancestral home town is called “Falling leaves return to their roots.”

This so touched his heart, Tang Ju Chuan personally donated the funds to send the deceased back to their hometowns. If the bodies were in remote areas and no workers were willing to go to pick them up, he would go there by himself, and would even clean the decomposed bodies himself before he put them in the wooden boxes and shipped them home.

Because of his great act of kindness, he was honored and respected by many in the San Francisco Bay area.

The biography of Tang Ju Chuan in the jiapu.

(Stories such as this are what make these jiapus and zupus so fascinating. It is one thing to know that a person lived and died between specific years. It is quite another thing to discover the choices they made, the lives they touched, and the things they valued most.)

![]() Here is Tang Ju Chuan in our FamilySearch tree.

Here is Tang Ju Chuan in our FamilySearch tree.

By such a father Tang Shao Yi was taught that with wealth and privilege came great responsibility to bless the lives of others. This was to be his lifelong practice as well.

Tang Shao Yi was sent to America to get a modern education — an initiative of the Qing dynasty to educate the children of China’s elite so they could help China succeed in a modern age. As a child he attended prestigious schools in Massachusetts and Connecticut, then Queen’s College in Hong Kong and Columbia University in New York.

He became a lifelong friend and loyal ally of Sun Yat Sen (also born in Hsiang-shan (Xiangshan) County) when he was sent as an emissary of the Qing court to negotiate a peace treaty with the southern provinces after the WuChang Uprising.

Dr Sun Yat-sen, right, first provisional president of the Republic of China, and Tong Shao-yi, first premier of the Cabinet of the Republic of China, in front of the Presidential Palace in Nanking (Nanjing) on March 25, 1912. [Photo courtesy commons.wikimedia.org]

Tang Shao-yi in 1931 [Photo courtesy commons.wikimedia.org]