Susan Chock Salgy

Chock Lun – publisher of the Chinese of Hawaii

While researching the Chock/Zhuo descendants from Guangdong who settled in Hawaii, our genealogist Louise Skyles discovered a little-known set of publications that proved to be extremely valuable at connecting families with their ancestral roots.

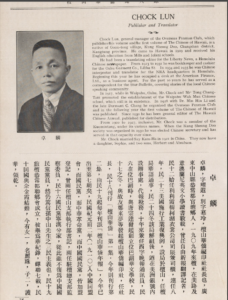

The Chinese of Hawaii 檀山華僑 (Who’s Who) was published by Honolulu: United Chinese Penman Club in three separate editions. Volume 1, 1929; Volume 2, 1936; and Volume 3, 1957. The publisher was Chock Lun of Guan Tang.

About the books

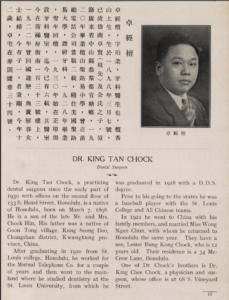

The books feature prominent Chinese residents of Hawaii who are notable for their contributions to Hawaii’s business, community, medical, and educational success. Since the majority of Chinese immigrants to Hawaii during the 19th and early 20th century came from the Guangdong/Canton region, a great number of the people featured in these books have their roots in Guangdong.

The Chinese characters coupled with the English version of the story provides vital genealogical data.

One of the most useful things about these books is the publisher’s decision to provide the information in both Chinese characters AND English. This reflects the practical reality that the generations born in Hawaii were unlikely to ever master the written Chinese language. The publisher understood that for the children to read about their parents and other Chinese community leaders, it was vital that the contents be provided in both languages.

This makes the books a fascinating resource that is accessible to genealogists like myself, who have a keen interest in knowing about the world my Chinese family inhabited in Hawaii. So if you have looked at one of the jiapus and gotten overwhelmed and a little discouraged by the relentless array of beautiful, but unintelligible, Chinese characters, you will love these books. In addition to the biographies, there are some outstanding essays that give rich insights into the way it felt to live as a Chinese immigrant in Hawaii in those years.

And most importantly, if you only know the way your grandfather’s name was pronounced and written in Romanized letters when he landed in Hawaii, these books offer the essential details that will allow a Chinese genealogist to connect him to his place in his clan’s jiapu: the Chinese characters for his surname, his father’s name, date of birth, and village of origin.

Without this, you are stuck hunting for a Cantonese surname that is spelled any way the ship’s steward, employer, or census taker heard it on any given day. But with this, you are searching for a surname character, which never changes, no matter how it is pronounced. That’s the magic of the Chinese writing system, and why modern Chinese people can read still documents written hundreds and thousands of years ago.

NOTE: The layout of the books reflects this dual citizenship approach. The page numbering starts at both ends of the book. The English content starts on the left end of the book and begins with page 1. The Chinese content starts on the right end of the book and starts on page 1 as well. (This confused me at first when I was flipping through the first book, but then I found their little note about it on the English side of things, and realized what they had done.)