Chock Chin’s store in Hanalei had a popular restaurant and bakery area in it. This establishment was a fixture in the community, feeding local villagers, visitors from the port, plantation workers and paniolos from the nearby ranches. The name of the Chock Chin Store was later changed to C. Akeoni, Lau Store and then Hanalei Store in 1931 after Chock Chin died and Mrs. Chock Chin sold the store to Charles Lau, a rice farmer who later farmed taro. The store remained open as a restaurant, meat market, and general store until 1941.

C.Akeoni was the Hawaiian-ized version of the name Chock Chin.

It was offered as an example of Chinese restaurants in Hawaii in a paper published in 2010. Here on page 114 we find Chock Chin and his C. Akeoni store described:

Franklin Ng, “Food and Culture: Chinese Restaurants in Hawai‘i,” Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America (San Francisco: Chinese Historical Society of America with UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 2010), pages 113–122.

The entire paper is very instructive, and helps us understand the world in which Chock Chin was operating. When I first learned about this combination restaurant/bakery/general store I found it rather unusual. However, this historical frame of reference puts it in context for me, showing this to be a well-established business practice at that period. If you’d like to read the whole report, download it here.

![]() Download Chinese America: History & Perspectives CHSA_HP2010

Download Chinese America: History & Perspectives CHSA_HP2010

Running the Restaurant

Chun Shee (3rd Chinese wife) was the cook, and Chock Chin was the manager and baker. They worked together to develop the menu, and his garnishing and presentation skills were used for special dishes and special occasions. He was always looking for ways to expand and innovate the menu, to introduce new dishes to his customers. This story from his daughter illustrates his constant quest for new recipes, and the way he encouraged his children to develop and expand their talents and try new things.

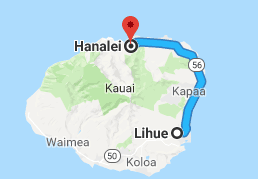

He was friends with Mah Lum Sook (the kids called him Uncle Mah Lum), who was the chef at the Lihue Hotel, about 30 miles from Hanalei. Daughter Janet recalls that whenever they would go to Lihue for their periodic family portraits, they would end with a visit to Uncle Mah Lum at the Lihue Hotel. His wife would entertain them at their home on the hotel grounds, and “Papa spent the rest of the day in the kitchen with Mah Lum Sook, observing, learning and tasting all kinds of cooking. I still remember those delicious roast beef sandwiches that Mah Lum Sook gave us for lunch.”

He was friends with Mah Lum Sook (the kids called him Uncle Mah Lum), who was the chef at the Lihue Hotel, about 30 miles from Hanalei. Daughter Janet recalls that whenever they would go to Lihue for their periodic family portraits, they would end with a visit to Uncle Mah Lum at the Lihue Hotel. His wife would entertain them at their home on the hotel grounds, and “Papa spent the rest of the day in the kitchen with Mah Lum Sook, observing, learning and tasting all kinds of cooking. I still remember those delicious roast beef sandwiches that Mah Lum Sook gave us for lunch.”

Janet said, “Maybe it was in that Lihue Hotel kitchen that Papa learned some new things from the baker. He was ever alert to try new ideas. He always encouraged us when we wanted to do something. Once I saw the plantation manager Faye’s cook make mayonnaise, and for the first time I ate potato salad. I had watched attentively and even asked to help him. That afternoon when I got home I told Papa about it and how delicious the salad tasted. He suggested that I try to make it. I had to use a fork to beat the egg yolk and oil together to make the mayonnaise because we had no beater. Papa and Mama watched and also helped to boil the potatoes and eggs. Finally, when I served them the potato salad, they liked it. Papa said, “Next time we cook lunch for the Wilcoxes, you make potato salad too.” Somehow I managed to convince Papa that the Wilcoxes would enjoy his Chinese food more!”

Interestingly, Franklin Ng’s description of Chock Chin’s creative restaurant fare actually cites roast beef sandwiches and potato salad as examples of non-Chinese, non-Hawaiian dishes he experimented with. As we see, the roast beef recipe came to them via Uncle Mah Lum, and their young daughter Janet had the honor of teaching them how she learned to make mayonnaise and potato salad from the plantation manager’s cook.

Their eagerness to adopt new recipes, and willingness to learn from their daughter, speaks volumes about the expansive, inclusive, nurturing, creative culture of their new-world home. This scene is difficult to imagine taking place in the home Chock Chin was raised in, where daughters were not invited to teach the father and mother anything, and families prized their old recipes and traditions above all else. It appears that by removing himself from China and the household where the old ways would prevail, Chock Chin found the freedom to reinvent himself, and create a new way of running a family that would have confounded his fathers, but was a great blessing for his wives and children.

Using the Restaurant to Teach the Children

Not only was this a great way to provide for the family, but it turned out to be a fantastic way to teach children vocational skills and life skills as well. In this respect, I believe it was similar to raising children on a farm, where the relentless demands of the animals, or the crops, provide children with a keen sense of duty, purpose, and commitment.

I have seen large families who have looked for ways to create this sort of culture in their city homes. For example, I became good friends with the Baird family who lived a block from my house when I was raising my little children in the 1980’s in Provo, Utah near the BYU football stadium. They wanted to live near campus so the husband, a Linguistics professor, could walk to BYU to teach his classes. But they worried about how they would be able to teach their 11 children how to really work hard at an unending job — even when you don’t feel like it — without the natural demands of a dairy farm or something like that.

They decided that a huge garden and orchard would be their solution. They bought two adjoining lots and used one of them to plant grapes, raspberries and a huge garden. The care of the garden, the harvesting and preserving of the produce, and the ongoing grinding of wheat and baking of 6 loaves of bread every day, became the endless stream of “work that must be done no matter what” that helped them teach their children what no amount of light chores and allowance can possibly teach. As Rey Baird told me, when I asked him if it was cost-effective to grow all those raspberries when you could buy them more cheaply: “I’m not raising raspberries, I’m raising children.”

Chock Chin understood that better than anyone. The memoirs of his children show that this restaurant — in addition to his many other enterprises — proved to be a wonderful environment to learn many important life skills. Each family member played a vital role in making the restaurant a success, and in so doing learned life-long lessons.

The children worked the cash register and delivered bills. One of the sons had the job of driving the freight wagon pulled by two white mules. The children learned how to calculate change, deal with customers, speak different languages, and serve, bus tables, and keep the restaurant clean. Since Mom and Dad worked there too — Mom as the cook, Dad as the manager and baker — it never occurred to anyone that you might not “feel like working” sometimes. Work was just part of life — it had to be done, and the examples of their parents set the standard of excellence.